How IBM Watson’s Machine Learning Builds Trust Between Dementia Patients and Caregivers via Storytelling.

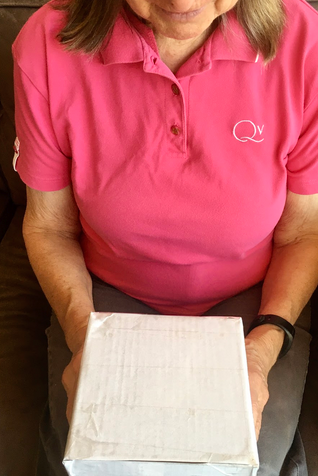

Caregiver clutching the cube, an interface designed to help treat dementia patients by populating surfaces with prompts.

Disclaimer

Curious how our team dynamic and project breakdown worked out? If so, I’ve marked some examples of how our team divided and conquered tasks.

This project couldn’t have been possible without the hard work of my peers, which I am incredibly thankful for! It’s also important to note that these are not all of the contributions that our teammates made; rather, they highlight just a few instances of how our team functioned as we embarked on the project.

You can quickly view those under these sections marked with a divider. They look like this!

Team Dynamic

〰️

My Contributions

〰️

Team Dynamic 〰️ My Contributions 〰️

Overview

Everyone loves a good story. But did you know that storytelling may be a tool that can help dementia patients?

The Cube is a studio collaboration with the IBM Watson Health Team that explores Watson's machine-learning capabilities to establish trust between a dementia patient and caregiver.

This intervention focuses on an often-overlooked stakeholder; the caregiver, and explores possibilities for an interface that helps dementia patients maintain autonomy and improve task adherence.

Timeline

Feb - April 2020

Research Question

“How might machine learning be used to effectively assist a caregiver in maintaining the autonomy of a patient through the stages of dementia and increasing caregiver custody? ”

Stakeholders

Team:

Gloria Jing, Jack Ratterree, Eryn Pierce

IBM Watson Health Team:

Debi Ndindjock, Aisha Walcott-Bryant

The Challenge

In 2020, IBM Watson’s Health Team approached our studio with a proposition. Their goal? – To explore Watson’s machine-learning capabilities in the healthcare space. Rather than produce a marketable product, IBM was interested in future-facing possibilities, delivered in the form of UX research, scenario videos, and prototypes.

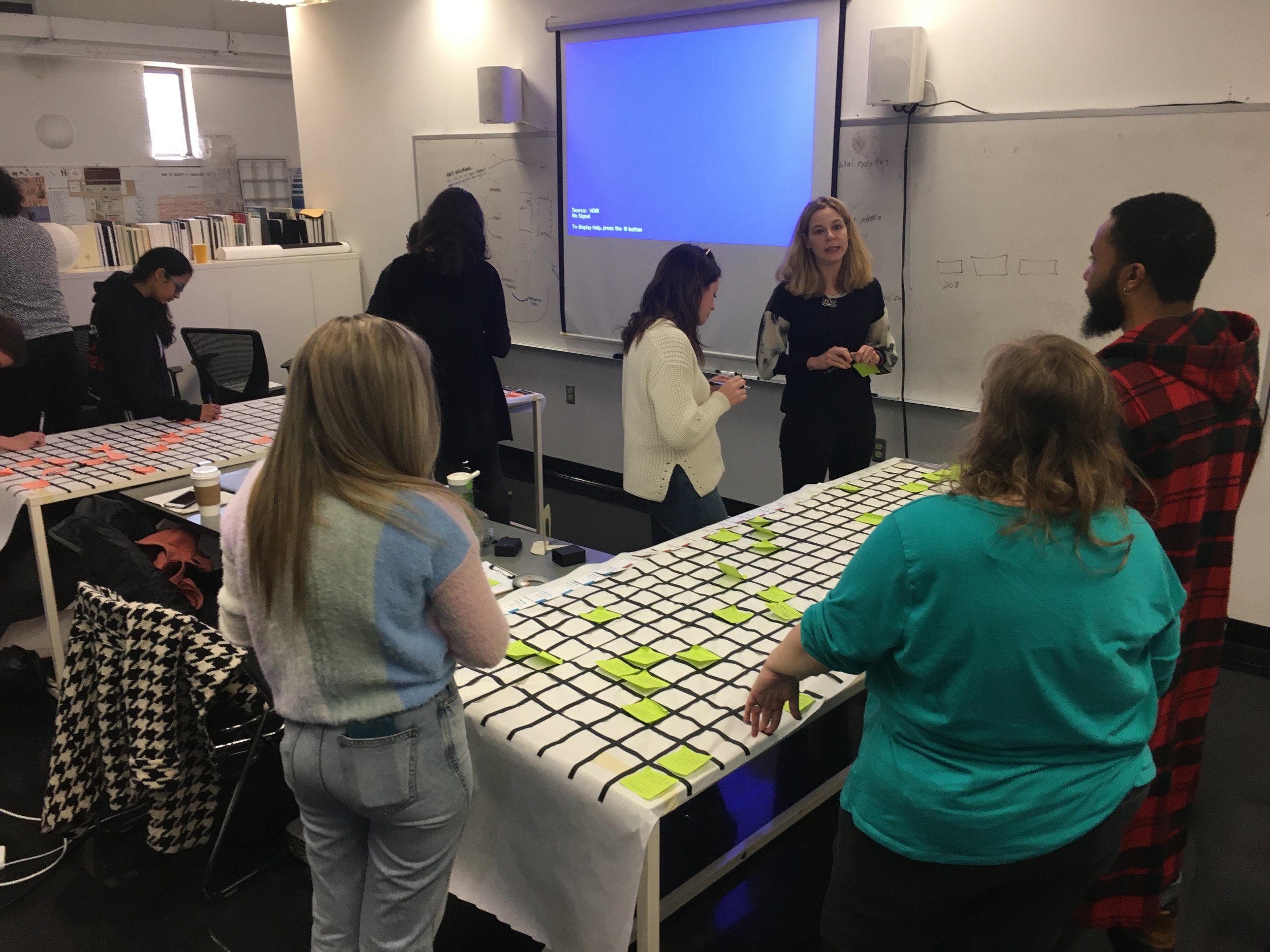

Design Studio students and professor gathering around a discovery matrix activity. Each axis of the matrix contains an element of a machine-learning principle, and we were asked to come up with pairings.

Pedagogical Tidbit

Often, companies will run similar studio project collaborations, in hopes of seeing student innovation to explore problem spaces that the company is interested in but don’t currently have the time or bandwidth to pursue projects.

With this in mind, our team got to work.

01: Project Kickoff

The initial brief led with this research question, focused on improving the quality of patient/doctor discussions:

“How might the design of an interface harness Watson capabilities to improve the face-to-face doctor/patient experience? ”

02: Core Ideologies and Discovery

To better understand how machine learning could impact the patient/doctor experience, our team conducted a series of discovery-based design exercises following a research led-mentality.

My Contributions

〰️

Team Dynamics

〰️

My Contributions 〰️ Team Dynamics 〰️

During the early research phases, the team gathered literature sources to review. Jack spearheaded the literature review front, while Eryn and I reviewed the sources and contributed our own.

Out of the 9 patient interviews, I conducted two interviews due to availability of patients. Eryn and Jack covered the other 7 between themselves since they were able to source more participants with a quick turn-around. Here, time was of the essence since the project was quickly moving forward, so the team prioritized interviewing patients they had contact with before branching out.

Excerpts from one of the patient interviews & literature review.

Throughout the project, our team adopted a research-led mentality, meaning that every deliberate decision we made was backed by data. “Research” could mean an extensive literature review to get an understanding of the problem space and to see existing interventions. Or it could mean an insight from one of the nine user interviews we conducted to narrow our problem space.

But, how do you begin to approach designing for an unpredictable, debilitating disease such as dementia?

03: Defining the Problem Space

Through our findings, we discovered that there are six stages of dementia. To scope down the investigation, we chose to focus on the third and fourth stages.

The six stages of dementia are:

1. Noticing change (2 years)

2. Making adjustments (1 year)

3. Shifting responsibility (2 years)

4. Increasing demand (2 years)

5. Full-time care (1.5 years)

6. End of Life (.5 years)

The six phases of dementia.

As the stages progress, dementia patients transition from noticing brief memory lapses within the first three years to needing full-time assistance at a care facility at the end of life.

Why not choose the other phases?

Stages 1 and 2 mark a period of discovery where patients identify that something is wrong but they are not sure that dementia is the cause.

At stage 3 and 4, the patient identifies that dementia is the issue and still maintains enough patient autonomy to benefit from design intervention.

In stages 5 and 6, patients are transitioned to full-time care, leaving little in terms of patient autonomy – in many cases, at the end of life, patients require assistance with eating or using the restroom.

Disclaimer

My statements above do not imply that there is no room for design intervention in the other stages. The statements above consider the team interest factors at the time along with project scope, which is what led to us choosing the third and fourth phases.

Within these phases, the disease has progressed to a point where family members who normally take care of patients start to feel the burden of responsibility for their loved ones and require extra help. Often, this means asking for outside help and calling upon professional caregivers, prior to full-time assistance.

04: Refining the Problem Space and Research Questions

Additional research uncovered an important, overlooked stakeholder – the caregiver. We re-framed our research question to empathize with the caregiver, creating personas and a user journey map to address key pain points.

Our user interviews revealed that both caregivers – whether in-home or professional – experienced obstacles as they tried to help navigate the complexities of dementia. Our team created two personas: Lynn, the primary family caregiver, and Tricia, the in-home nurse professional caregiver – to understand the caregiver’s needs and help identify specific points of intervention to care for the dementia patient.

Lynn: Primary FAMILY CAREGIVER

Lynn, like many others, didn’t choose to become a caregiver. Rather, she was involuntarily thrust into taking care of a dementia patient. In Lynn’s case, it was her 86-year-old mother. Lynn struggles to juggle her job as a high school teacher, her household responsibilities, and her duties to her mother. Lynn wishes to:

Understand medical information and keep her family connected while making sure her mother is safe and comfortable at home.

Gain confidence as the unpredictability of her mother’s illness and maintaining a support system makes her feel stressed and under-informed.

Tricia: professional caregiver

Tricia, who serves as the in-home nurse professional caregiver, faces different struggles. While she is an experienced caregiver, she struggles to:

Build trust with the patient and their family and determine when information is appropriate to explain.

Act as a mediator between the patient, their family, their doctor, and their medical information as it makes her feel out-of-touch and unstable.

Since Lynn and Tricia’s experiences differed as caregivers, our team created a user journey map to understand the differences between the two.

Through these insights, our team further refined our research question, arriving at:

“How might machine learning be used to effectively assist a caregiver in maintaining the autonomy of a patient through the stages of dementia and increasing caregiver custody?”

User Journey Map describing the individual caretaker’s journey. The top segment represents the family caregiver, while the bottom represents the hired caregiver’s pain points. Individual colors correspond to the respective caregivers emotions. Blue connotes a positive emotion while red symbolizes a negative one. Black signifies a neutral state.

My Contributions

〰️

Team Dynamic

〰️

My Contributions 〰️ Team Dynamic 〰️

I was in charge of creating the user journey map, which I based off of the research and personas that the team created and gathered. It describes how a family caregiver & hired professional caregiver’s pain points differed from each other as they navigated their day.

“In most cases with dementia, long-term memory is intact until the very end of life. So, getting people to tell stories from their own past to think in the moment is helpful in grounding them in reality before you have a conversation that requires rational thought. There is potential to see the progress of the patient — not just in the patient’s deterioration.”

05: Further Research and Critique Preparation

Surprising insight from user interviews revealed that dementia symptoms could be exacerbated by low iron blood levels associated with anemia. Though anemia is treatable, patient adherence to taking iron supplements is volatile.

Now that we had shifted our problem space, we re-interviewed a few users to develop a better understanding of how caregivers treated their patients.

Surprisingly, we discerned that there was a clear link between anemia and dementia. Low iron blood levels ( a hallmark sign of anemia) increases the risk of mild cognitive impairment further impacting memory. Most importantly, our team found that anemia was treatable by increasing the patient’s iron levels.

The simplest way would be to have the patient take iron pill supplements and raise their iron levels. However, this posed an additional problem. The patient’s willingness to adhere to tasks fluctuates rapidly depending on disease progression. He or she may only need verbal cues one day but suddenly require written or visual cues the next.

06: Concept Development

To address this unpredictability and fluctuation in task adherence, our team presented two concepts to the IBM Watson Health Team for critiques. Concept One focused on connecting storytelling and trust to task adherence. Concept Two focused on mediating patient and caregiver discussions to aid in decision making. After further discussion and research, we chose the former.

Concept 1

What if there was a device that improved patient-caregiver connection and task adherence through storytelling? It would:

Build trust, empathy, and rapport between the patient and their caregiver.

Generate fodder for discussion to enhance information delivery and, thus, improve understanding and retention.

Track disease progression and adapts interface accordingly through user touch points.

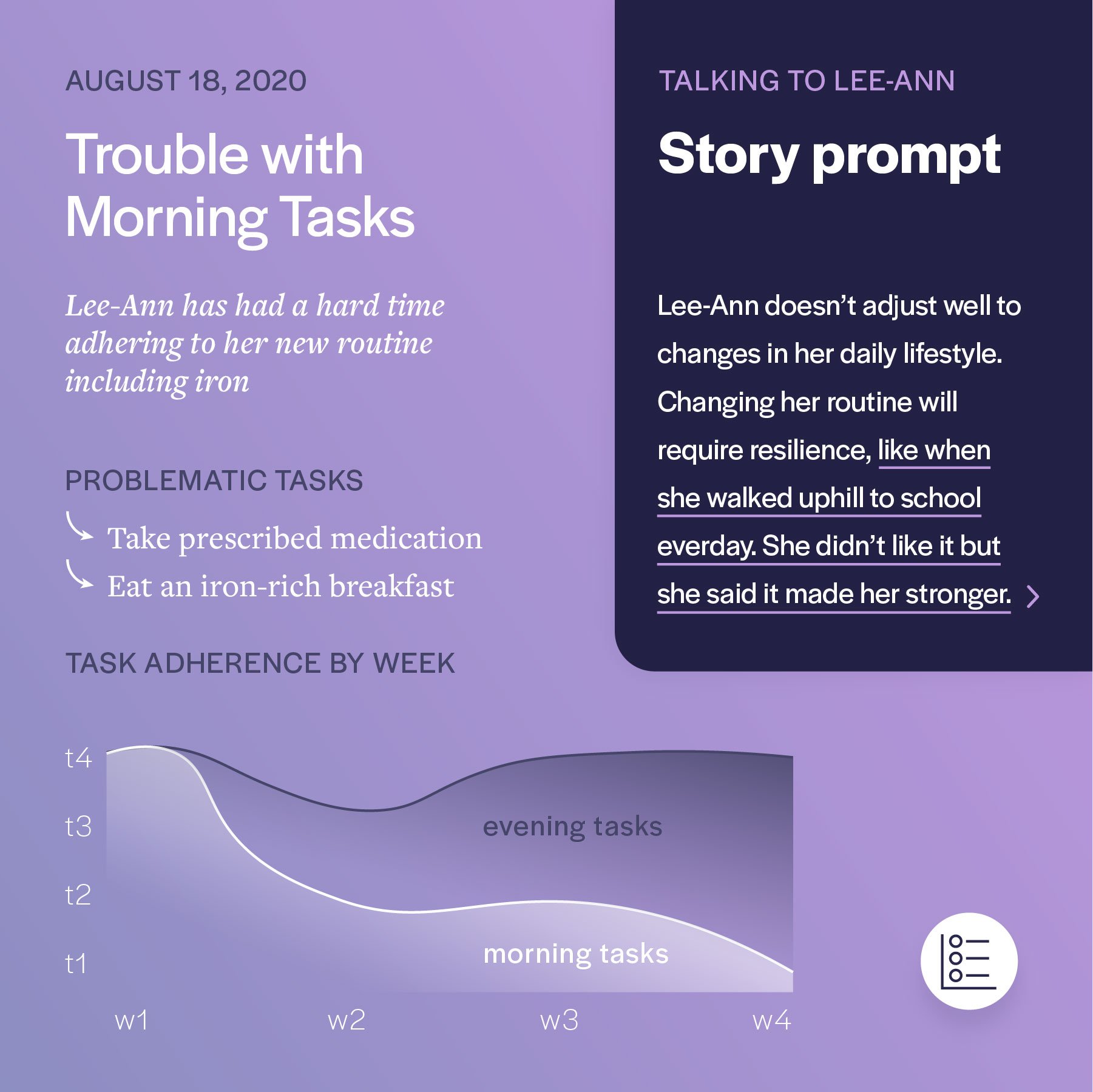

Concept 1 Storyboard. Main premise depicts how a caregiver would utilize the cube by telling a narrative and then transitioning to daily tasks. Storyboard also describes how the patient would interact with the cube on their own until the next visit they have with the caregiver.

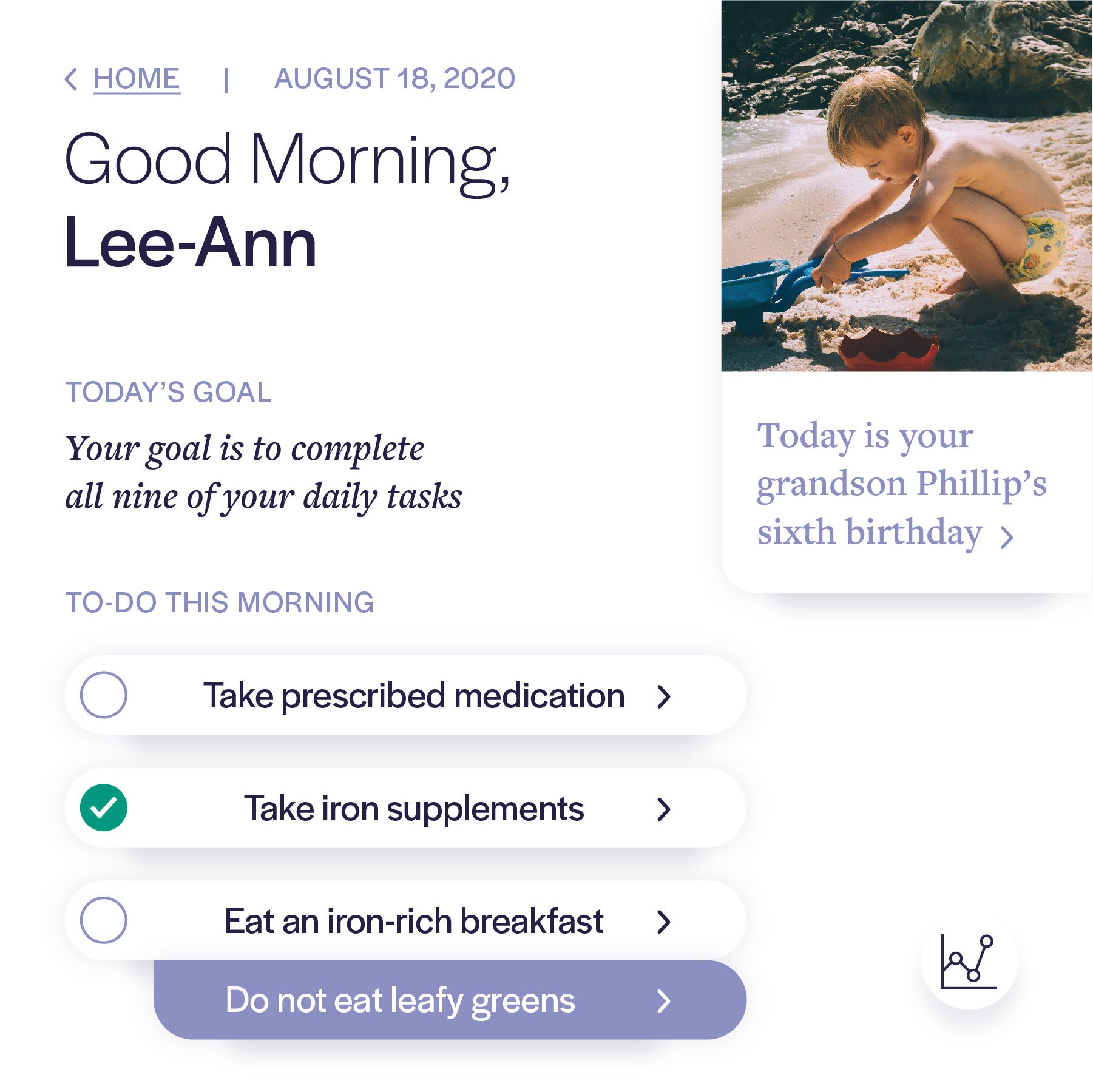

Concept 1 Wireframe. These screens correspond with the labeled numbers (1) and (2) in Concept 1 Storyboard. Wireframes depict how UI portrays important daily tasks and family stories in an early iteration within the wireframe stage.

Concept 1 storyboard. This storyboard builds upon concept 1’s storyboard and describes the ecosystem that allows the doctor to easily track patient progress.

Concept 1 wireframe. These screens correspond with the labeled numbers (3) and (4) in Concept 1 Storyboard. The delivery prompt is highlighted alongside a more comprehensive patient overview and task progress.

Team Dynamic

〰️

My Contributions

〰️

Team Dynamic 〰️ My Contributions 〰️

Jack & Eryn designed the wireframes here. I was also in charge of designing some pre-mockup wireframes that predated these wireframes as well just to give Eryn and Jack an idea of where to take the concepts. For these iterations, I created all of the graphics related to the storyboards, since Jack and Eryn were not as confident in sketching them out.

We decided as a team that it would make sense for me to draw out all of the storyboards after discussing how the layouts would be and we collaborated on how that would link up to the UI elements that Jack and Eryn conjured up.

Concept 2

What if there was a device that could understand and advocate for a patient to aid in the caregiver’s decision-making? It would:

Extend the autonomy of the patient.

Mediate discussions and composes questions to reduce the burden of making choices.

Break impactful decisions into manageable elements and talking points to ease communication between the patient and their extended family members.

Concept 2 Storyboard. Main premise discusses helpful machine learning suggestions that the interface would be able to aid the caregiver during her patient visits. Furthermore, it describes how other family members can become more proactive in their care and mediate discussions amongst all parties.

Concept 2 wireframe. These screens correspond with the labeled numbers (3) and (4) in Concept 2 Storyboard. Here, UI shown details what recommendations and consolidations that the family has discussed thus far.

While both concepts were promising, our team decided to choose the first concept based on innovation, subject matter interest, and clearer understanding of how to envision the use cases for the product.

“The only thing better than visual aids would be 3D models to help explain something. It engages spatial thinking that many people with certain kinds of dementia have an impairment. Depth perception and distances are problems for them, walking is difficult for them, so making them work in this area of the brain is important.”

07: Prototyping

We got to work refining our concept, performing rounds of iterations and user testing to ensure that our concept was on the right track.

User testing images, depicting the prototype of our cube model. It was important to have a mockup of how large the size of the cube was and how it might feel interacting with the cube, which is why we created a prototype.

Insights

3 of 3 testers thought the cube was a good concept

“This is a whole different area you are working in is their spatial cognitive response and long term memory with the photos. You are also doing short term memory by having pictures on different surfaces and having patients remember where they are.”

“It was nice to hold. It’s a nice size. It’s a nice shape and it’s easy to play with.”

2 of 3 testers wanted to have access to all the data at once

“I’d expect to see a clear definition of what tasks need to be achieved

and what the tasks are.”“I want to see the whole task list at once with a schedule. There are six undefined tasks here. I don’t have time to look at more than one screen.”

Things to Keep

The Cube

Spatial Thinking

Short-term memory engagement + long-term memory engagement

Shareable and fun to play with

Storytelling feature

Natural & helpful prompting

Caregiver learns about patient

Building the patient-caregiver relationship

Things to work on

Data/Content

More data and clearer interactions

Display all the data in one place

Contextualize data within the tasks

Make the type bigger

Extra features

Add a notes section

Shows a history of the progress

After considering feedback from our user testing and incorporating it into the final product, our team also considered specific details as we neared the end of the project.

During this phase, for example, it was important to scrutinize every detail. Everything from the typeface we chose to language we employed was vital.

For example, since the cube had to be able to be viewed from multiple parties, and understanding that people with dementia tended to be older adults, we had to make sure that the typeface was large enough to be understood.

An early iteration example of how we deliberately chose a larger typeface to be easily readable by all parties viewing the cube.

It was also important that language was not disparaging to the patient, and a subtle change in body copy would drastically change how the patient and caregivers were interacting.

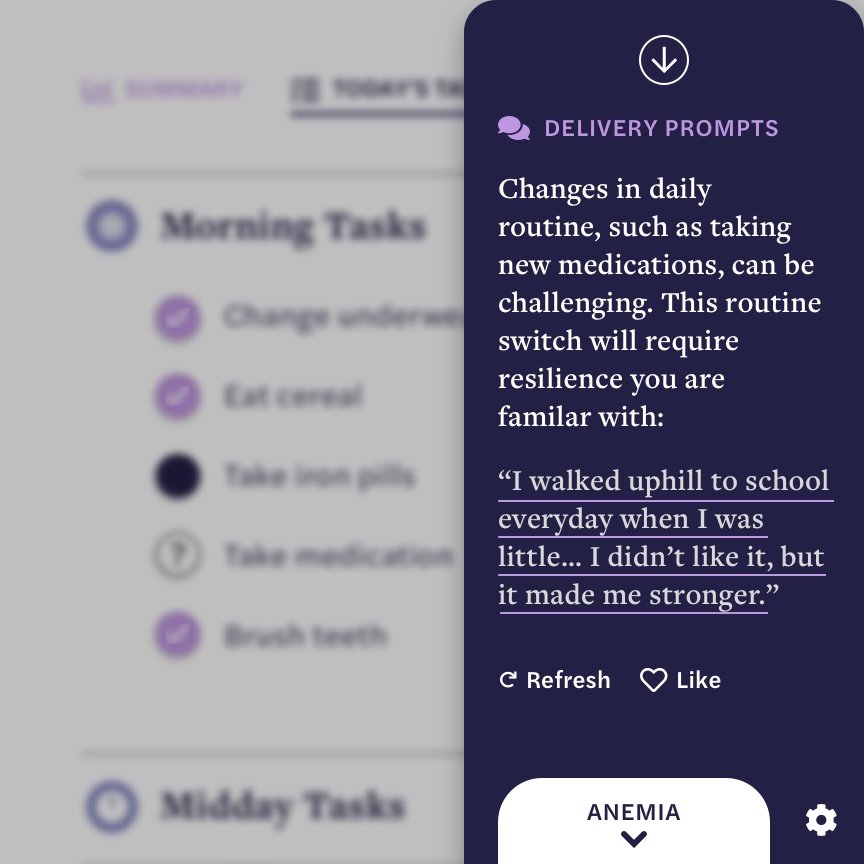

Here, a slight change from the body copy denotes a shift in perspective. Version 1 and Final differ based off of language. Version 1 addresses the caregiver by mentioning Lee-Ann (the patient) by name and uses more negative language such as “doesn’t adjust well” or “She didn’t like it…”

In the final version, the interface incorporates more neutral language that can address the patient or caregiver with “Resilience you are familiar with…” While this is directed more towards the patient, removing the negative language considers how the patient would interact with the interface rather than just the caregiver in version 1.

Moreover, we also simplified the interface for convenience.

Team Dynamic

〰️

My Contributions

〰️

Team Dynamic 〰️ My Contributions 〰️

Our plan of action with the script and tasks to do for the team.

Video showcasing primary animations of the interface without cube flips.

An example of how the cube animation and videography came together. Due to our team’s capabilities and strengths, I was primarily in charge of creating the 3D animations in blender and writing and recording my voice for the script. Eryn filmed the video with the caregiver, and Jack stitched the final video together. Throughout the process, our team worked together to figure out how all of the pieces would seamlessly flow unto each other.

It was also during this time that the COVID pandemic had emerged. Therefore, it made sense to delegate tasks so that hand-off would be smooth. For example, while all of our team members had the ability to create animations, it made sense to designate one person to be in charge of the animations as we didn’t have the opportunity to collaborate in-person to handle specific assets. Furthermore, dealing with multiple assets and different time frames would be possible, but was not the most effective use of our time.

I was also the only member who was confident in working out the modeling specifics of how to get the cube to turn (which required image mapping and animation within blender) which was a large bulk of the project’s premise.

Scenario / Key Features

Our scenario video plays out how our cube prototype would function; the caregiver would prompt the patient with storytelling, and then address key action items such as taking iron level pills to aid task adherence.

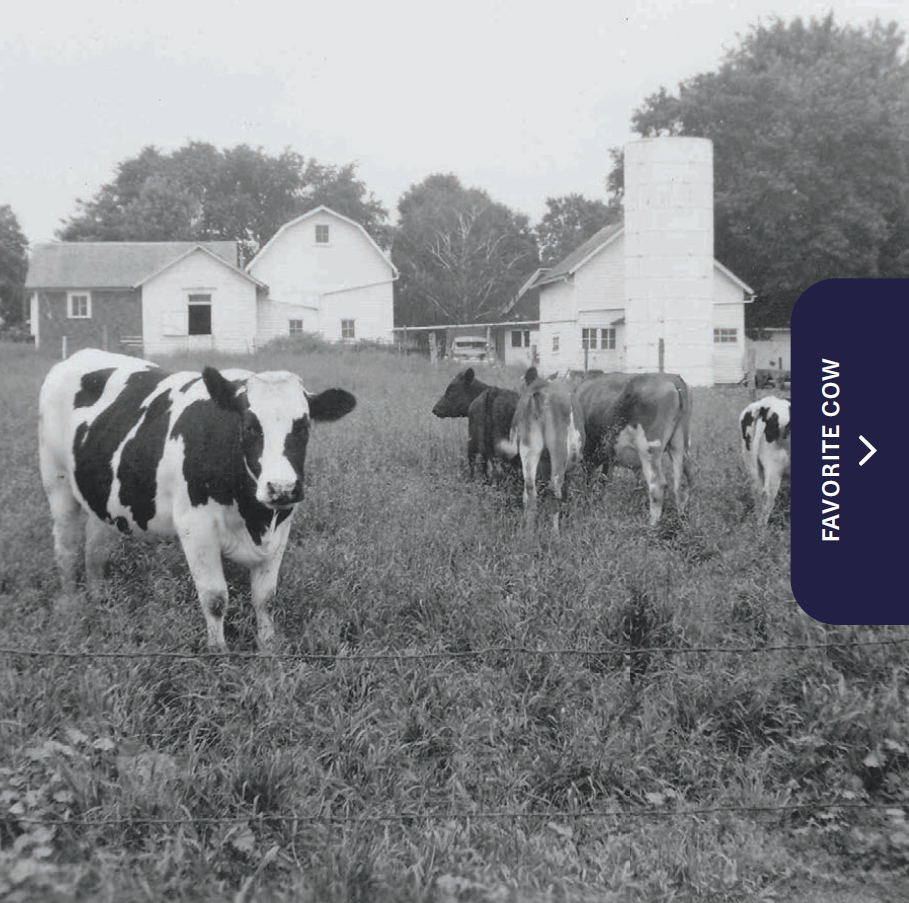

We begin today in the home of Lee-Ann. She is an 83-year-old patient who is experiencing dementia and anemia. To ensure that she is doing fine, she has weekly visits with Tricia, a professional caregiver….

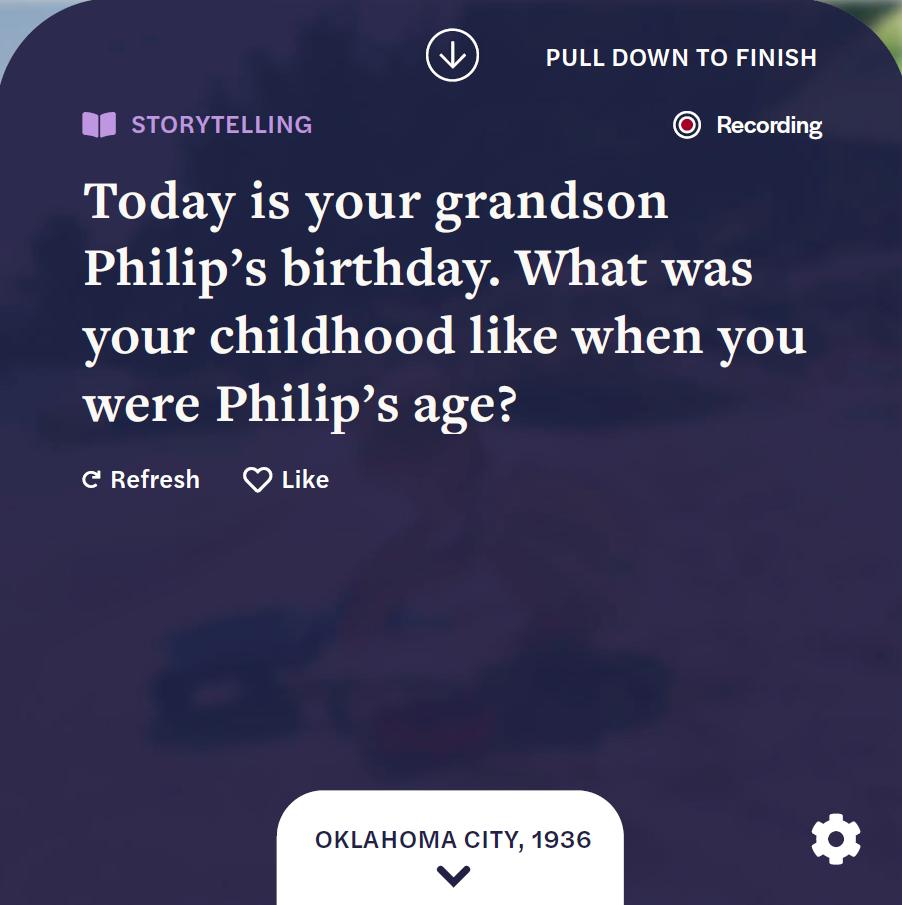

Tricia engages Lee-Ann with a story, asking her to recount her childhood. As Lee-Ann tells the story, the cube begins recording and provides images as ways to guide the story. These prompts can be manually modified or automatically adjusted to the progression of the disease, as multiple storytelling sessions ensue. Tricia can also supply feedback to the cube, adjusting and editing notes to train IBM Watson’s Machine Learning to provide more relevant prompts in future.

After the storytelling is complete, Tricia reviews Lee-Ann’s daily tasks and reminds Lee-Ann to take her medication. If the caregiver is experiencing any trouble with relaying that information, the cube will adjust. For example, if Lee-Ann shows signs of confusion and needs understanding of why iron pills are relevant to treating the disease, the cube will pull up helpful videos to explain the issue, easing the caregiver’s burdens of having to consistently repeat the information.

Beyond the initial cube touchpoint, we also envision an ecosystem related to caregiving, where the caregiver, patient, or family members can help manage the disease through mobile, desktop, or other smart applications.

Gallery of UI progression as the caregiver interacts with the patient via storytelling.

Overview of the ecosystem that the cube resides in. Touch points involve the caregiver, the family member, and the patient with examples of what activities each party can do.

During the storytelling portion of the visit, the cube will begin auto recording the activity. After the caregiver and patient finish, the cube prompts the caregiver to decide whether or not they wish to archive the story. With specific information prompts, the cube’s machine learning will configure the information delivery system based off of responses that the caregiver provides.

Here, the cube will be able to address aspects such as prompt complexity that depend on the stage of the disease. When the patient has reached more of an advanced stage of dementia, questions will adjust to incorporate less dependence on memory and source of recall.

08: Insights and Future Directions

With our design intervention, the cube introduces new spatial and storytelling considerations to address dementia. Furthermore, it focuses on an often-overlooked stakeholder, the caregiver.

Beyond this investigation, our team reflected and asked:

How could this 3D spatial system be used in other contexts?

How could our device adapt to the entire disease and beyond?

How can machine learning navigate the nuances of dementia?

Metrics of Success

Since this was a speculative project projecting future scenarios, the metrics of success differ from a marketable product.

Metrics here were delivered in the form of final deliverables, breadth of discussion and ideas generated through discovery & formation of research plan

Projects were routinely scrutinized via classroom studio & multiple IBM critiques. Adjustments and iterations were consistently made throughout duration of project based off of feedback

If this were a real product…

Delivery and support might look like:

Creating a research plan

Determining specific metrics of success (such as task completion rate) with stakeholders

Maintenance of product with routine check-ins with users to ensure that the product is providing value to patients, caregivers, doctor, and family members.